Witchcraft in Japan

Japanese folklore is full of magical creatures of tales of persons with mystical abilities. These people aren't referred to as witches per se, the word witch comes from European vocabulary, a single title to encompass all manner of people suspected to have mystical powers

In Japan, they have a much larger syllabus of magic and lore, each category referring to specific characteristics, each with their own stories and relationships with the mere mortal

So let's get into it

Episode: File 0049: Witch Please Pt.2

Release Date: October 29 2021

Researched and presented by Cayla

Familiar Witches

There are many tales of witches who have animal companions. The two most common being, those employ snakes and those who employ foxes

Fox Witches

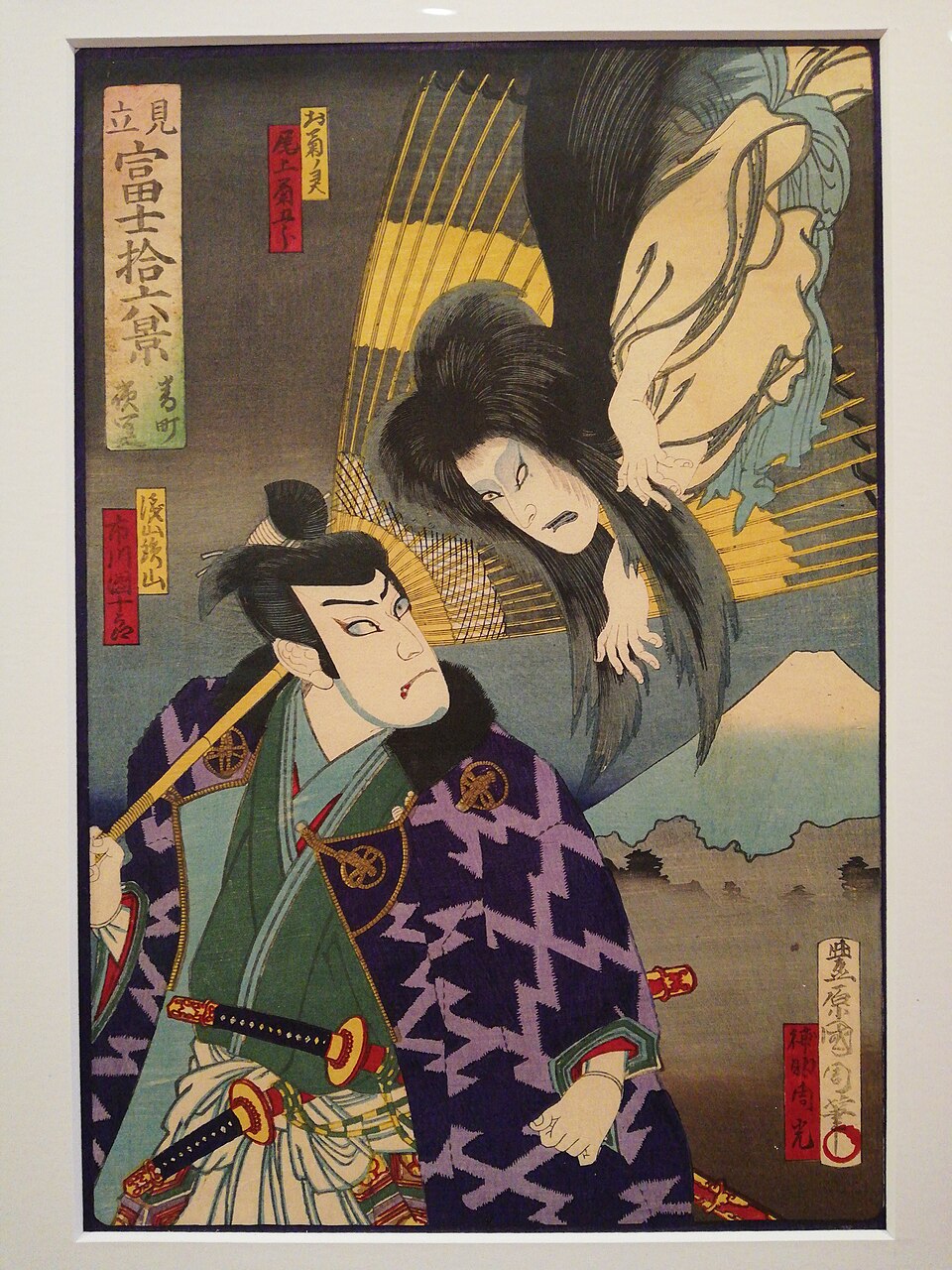

The fox is an incredibly important and prominent character in Japanese folklore, you may be familiar with the term kitsune, which is Japanese for fox. The kitsune itself is rich with lore and mythology and finding the line between kitsune and witch lore is nearly impossible, with their mythology intrinsically intertwining the two in a tangle of mystery and mysticism

I want really give kitsune fables their deserved attention, so I am going try and specifically talk about the stories that land more on the witchcraft side vs the powerful and mythical beasts of legend, just know that in Japan foxes have a very rich history and symbolism, and the fact that this is tied to witchcraft is really not that surprising

In the lore foxes can be tricksters, but they can also be faithful guardians, friends and even lovers. But in most witchcraft stories, foxes serve as familiars to witch. The Edo period 1603-1867 was the height of superstition, so tales of witches and their fox companions became quite prevalent

There's two ways that someone may obtain a fox as a familiar: through inheritance or through a deal

Through a Deal

Let's talk the latter first: known as kitsune-tsukai or kitsune-mochi, these are fox witches who made a deal with a fox so that it will enter their employ, typically in exchange for food or daily care in return for the fox's magic powers.

Now it's important to note that while some of these agreements could be mutual, there are also many tales where the witch tricks the fox into their service. There's even something known as the Izuna rite, where the witch would capture a pregnant fox and tame her, and take special care of the kits when they are born. When she and the kits are strong enough she will leave, but will ask the witch to name one of the kits, that kit will always be in the witch's service

While fox alignments tend to be all over the map, once a fox enters the employment of one of these witches, they become a force of evil and are to be feared. The witch will have their fox companion to help achieve their goals, often in a covert manner. The powers a fox may have is quite broad and you can understand why they'd be good companions for witches

- possession

- generating fire or lightning

- willful manifestation in the dreams of others

- flight

- invisibility

- the creation of illusions so elaborate as to be almost indistinguishable from reality.

Some tales speak of kitsune with even greater powers, able to bend time and space, drive people mad, or take fantastic shapes such as an incredibly tall tree or a second moon in the sky. Other kitsune have characteristics reminiscent of vampires or succubi, and feed on the life or spirit of human beings, generally through sexual contact.

The witch will use their powers to trick people or overwhelm them to get whatever they want, but most feared of all fox powers is their ability to possess people

What a witch could do with a possessed person could be as nefarious as ruining their lives or leading them to their deaths, or as scammy as the witch showing up and offering the exercise the person for a fee (without revealing their identity)

Hereditary Foxes

On the hereditary side, there are families that are thought to have special relationships with fox spirits. The families often pray to and serve these spirits to watch over them and the people they care about, bringing them prosperity and help with the harvest. Each generation is taught the rituals of their fox spirit and fox spirit families do not marry into non-fox spirit families.

While these fox spirits sound a lot more benevolent than the witch familiars, it is still said that the families can pay tribute to the fox spirit to take revenge on their enemies and thus these families often aren't trusted

These families found it difficult to sell property and do business with regular townfolk, and as the fox spirit was thought to be passed down through the women, the daughters had a hard time finding husbands

Being perceived as a fox spirit family could ruin your life and the lives of all your offspring. During the Edo period it was common to do extensive research into family trees of potential partners to ensure there was no fox spirits in the family. If a family was identified as a fox family, the town may raze their house and banish them

I'll give you some

guesses as to which families were most frequently thought to be fox families: the untouchables: the impoverished

and undesirables of Japan

Today Burakumin is used as a collective term for all

these undesirable groups. This classification began to show itself in the feudal era, with discrimination against beggars

and people who worked in kegare

(defilement) jobs (such as executioners, undertakers, slaughterhouse

workers, butchers, or tanners)

Like having a fox spirit, this reputation was hereditary, essentially making a caste of people that were considered the bottom of society. By the Edo period a strongly regimented class system was in place, and the burakumin became victims of severe ostracism and discrimination. So accusing a burakumin family of being a fox family was a good excuse to chase them out of town, as no one wanted such undesirables. Burakumin were forced to live in their own villages, similar to the ghettos, and this discrimination, while not as severe, still exists today

In North America, it's hard to imagine anyone caring that your great great great great grandfather had been a butcher, chances are you probably wouldn't even know, never mind anyone else. But Japan has been keeping some form of census since the 6th century

Over the centuries the stringency of these records and who was eligible to be included varied a lot. But in 1872 the current registration came into place. Known as koseki, these records serve as birth and death certificates, marriage licenses and a census, making this records highly valuable, especially since every Japanese citizen has one. In fact if you don't have one, you're technically not a Japanese citizen as you cannot prove that at least one of your parents is Japanese. There was a case in 2014 in Japan where a family was found harboring a 17 year old child that had NEVER been registered, denying them access to healthcare and education

Back to the Burakumin. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the class system was abolished, just in time for the koseki to come into play. Most people at the time were recorded as commoners, but there were many burakumin that were recorded as "new commoners" indicating their previous status of being less than a commoner, thus discrimination didn't stop

Since its introduction there have been many reforms to the Koseki. Up until 1974 it was required to bring your koseki to job interviews and you know that your partner's parents would want to see it if you were to ever consider marriage. Thankfully by 2008 the only people that can view your family's koseki is those in that family (with exception to legal institutions under specific circumstances)

Despite efforts to reduce ways that the koseki could be used for discrimination In 1975 the Buraku Liberation League was tipped off about the existence of a book called "A Comprehensive List of Buraku Area Names" a 330 page handwritten book that had extensive records of Burakumin families and their addresses. The preface of the book says this

"At this time, we have decided to go against public opinion and create this book [for] personnel managers grappling with employment issues, and families pained by problems with their children's marriages."

The book was being sold in the streets for anywhere between $50-$500 (in 1975). It was found that over 200 large companies (including Toyota, Nissan and Honda) had purchased copies of this book. While sale and production of the book has been banned, illegal copies still exist

Talk about making it hard to escape your past. All it takes is one burakumin in your lineage to effect how people see you, even impacting your ability to find work

It is said that over 60% of the Yakuza is comprised of burakumin descendants. Turning to crime to find work, especially in the 1960s when organized crime was at its peak in Japan. But that was still so long ago, are people really still being affected by this?

In 2001 there were two

candidates for a political party that were up to be considered in the

next election for prime minister. When

out of nowhere one of them, Hiromu Nonaka

withdrew from the race. Years later it would be found out that the reason he

withdrew was because he had overheard his opponent

saying there was no way they would let a Burakumin

become prime minister

Dakini-Tens

There is one other magical fox related entity known as Dakini-tens. These are female witches that appear in the form of or riding a white fox

The Dakini-ten entered Japanese culture with the introduction of Shingon Buddhism. As Buddhism traveled through Asia it acquired many stories and practices that reflected the cultures it passed through. Really this is super fascinating and one day I want to cover it, but that's for another time

Dakinis existed in buddhism prior to its arrival in Japan, seemingly linked to hindu folklore. During the Heian period in Japan, the dakini image was mixed together with images of foxes and half-naked women, acquiring the name Dakini-ten

And thus this figure entered the culture and became a powerful symbol

In the Middle Ages, the Emperor of Japan would chant before an image of the fox Dakini-ten during his Enthronement, and both the shōgun and the emperor would venerate Dakini-ten whenever they saw it, as it was a common belief at the time that ceasing to pay respects to Dakini-ten would cause the immediate ruin of the regime.

Snake Witches

Tobyo Mochi-Having Snakes

Snake witch stories seem to only come from Shikoku, a small island off the coast of Japan and in the Chugoku district. While considered to be the 2nd most prevalent witch familiar, I had a hard time finding information about them specifically. But there is one story that came up frequently in my research:

Jakotsu babā

"There is an old woman from in northern Funkan-koku, China. In her right hand she holds a large blue snake, and in her left hand a red one. The people of this country call her the Jakotsu Baba-The Old Snake-Bone Hag. They say she is the wife of Jakoemon (Five-Snake Emon), and that she holds vigil over the family tombs. She is sometimes called the Jagoba-the Five-Snake Woman- depending on the dialect of the region."

Cat Witches

Unsurprisingly cats are tied to witches even in Japan. Centuries ago it was a common belief that young women should not visit temples after the sun went down. The story goes that they would be approached by a kindly old woman, who would lure the girl home and then into her true witch form and devour the girl.

It was thought that cats that hang around temples are these witches in hiding, waiting for night to pounce

Necromancy and Shamanism

While necromancy and shamanism are generally considered entirely different classes from witches and wizards, I don't care about your rules, they used magic so I am here for it

Like nearly all cultures, stories of individuals that can talk with the spirits have been in Japanese folklore since the beginning of the written word. There are so many kinds and different stories, I could never cover them all so I have narrowed it down to the ones we have the most information and are still prevalent today

Miko (Mikoism)

Mikos, also known as a shrine maidens or priestesses. In ancient times, their role was to get the messages of the gods (oracles) and convey them to other people, but in the modern age it has changed to a role in shrines served by women.

Women were priests, soothsayers, magicians, prophets and shamans and they were the chief performers in organized Shintoism.

Mikos performed so many diverse functions that classification is difficult. Nakayama says that much of the origin of government, economics, literature, stage, etc., is from the miko. However, he makes a basic distinction between shrine attached and non-shrine attached.

Their goal is to make sure happiness is spread throughout society, and to remove any evil energy that resonates inside our souls. Mikos were important social figures early in history, and were associated with the ruling class of Japan. Their presence meant a lot to the community, as they would perform sacred ceremonies to ensure that those in charge would be guaranteed a humble passing into the spiritual world.

Historically

Certified miko earned her living by performing kuchiyose (invocations) but they were slaves, such as geigi (geisha) and shogi (prostitutes), whose revenues went to their masters. The modern government banned this type of business, considering it equivalent to human trafficking.

In 1873, the Ministry of Religious Education banned all acts requesting oracles through the invocation conducted by miko outside the shrine. This is called Miko Ban. some continued to operate in various ways through participation in traditional shrines or new schools of Shinto. Some shrines started to hire miko as a role to support Shinto priests.

In the modern age, miko are women who work for shrines mainly through the role of routinely supporting priests and occasionally performing kagura (Shinto music) and mai (Shinto dance). Miko need neither certification nor qualification, basically any woman can serve as a miko as long as she is mentally and physically healthy. Since professional miko are mostly the daughters of priests, their relatives or those who have connections to the shrine, shrines do not publicly seek many professional miko (and generally, only large shrines can afford to hire them)

Tools

Traditional tools that you'll normally see are the Azusayumi, or Catalpa bow, Tamagushi or Sakaki-tree branches, and the Gehobako. which is a spiritual box containing various sacred items such as Shinto prayer beads.

In the Modern World

In the anime Sailor Moon, Sailor Mars plays the part of a miko in her civilian form using various spells to dispel evil with an Ofuda to protect those around her. Ofuda can be found in various shrines along with households all across Japan and are mainly used for protection against evil spirits.

The more contemporary mikos are typically found in shrines such as the Ikuta Shrine in the Chuo Ward of Kobe, Japan, and is actually one of the oldest shrines in the entire country dating back to the 3rd century. Mikos now generally serve as assistants at shrine functions, perform ceremonial dances, offer Omikuji fortune telling, and sell memorabilia to passing tourists.

Himiko

Queen Himiko is the earliest ruler in Japan that can be verified as real person and is thought to have lived between 189-248. She was chosen as ruler by her people after 70-80 years of warfare. It is said that her staff was entirely comprised of women except one male that was her ambassador and her brother. It is thought that she ruled for 50-60 years

She presided over and was recognized as a rule in over 100 "countries" (Japan)

One of the most interesting things about Himiko, is that she either goes unnamed or is purposely excluded from all of Japan's oldest historical records. The reason we know about her all thanks to the historical records of China and Korea. It is suspected that since the first historians in Japan served the imperial government, they purposely chose to pretend she never existed. This makes it hard for us to have much concrete information on her or her rule

Yamabushi

Yamabushi are Japanese mountain hermits or monks believed to be endowed with supernatural powers.

For more than 1,400 years, Yamabushi monks have been walking Japan's sacred mountains, believing that this harsh natural environment can bring enlightenment.

Their origins can be traced back to the solitary Yama-bito of the eighth and ninth centuries. There has also been cross-teaching with samurai weaponry and yamabushi's spiritual approach to life and fighting.

They lived harsh lives, alone in the mountains, challenging themselves to the harshest environments and trials. They were strict followers of Haguro Shugendo, a religion that's a combination of shinto, buddhism, daoism and folk shamanism. They developed their own forms of cooking and became completely self-sufficient using what the mountains give them, sometimes not coming in contact with society for months or even years. Deeply in touch with nature and adept martial artists the yamabushi were figures of myth and legend to the common folk, it's thought they were the inspiration for the mercurial mythical creatures called Tengu

When all hope seemed lost they were often sought after for their healing skills and arcane knowledge. They were also known to serve as mountain guides since medieval times

It was not uncommon to see yamabushi accompanied by Itako, sometimes even as wedded partners.

As their reputation for mystical insight and knowledge grew and the degree of their organization tightened, many masters of the ascetic disciplines began to be appointed to high spiritual positions in the court. Monks and temples began to gain political influence. By the 13th and 14th centuries. They assisted Emperor Go-Daigo in his attempts to overthrow the Kamakura shogunate, proving that their skills as warriors were commensurate with those of the professional samurai armies against whom they fought.

Several centuries later in the Sengoku Period, yamabushi were among the advisers and armies of nearly every major contender for dominion over Japan. Some, led by Takeda Shingen, aided Oda Nobunaga against Uesugi Kenshin in 1568. Eventually Nobunaga crushed them and put an end to the time of the warrior monks.

Today, unlike their Itako sisters, the yamabushi are still going strong with over 6,000 members. But most of these practitioners don't do this full time

Itako / Ichiko / Ogamisama

Japan has long associated blindness with spiritual powers, after the introduction of Buddhism, it was considered evidence of a karmic debt. These beliefs lent an aura of "ambiguous sacred status" to the blind.

Originating in Aomori prefecture in northern Japan. While the exact origin of Itako is unclear, research points to the days of prehistoric Japan, when many villages were led by female shamans

The itako are first referenced in poem of the ancient Nara period (710 - 794). Anthropologist Wilhem Schiffer describes a local legend about the practice of recruiting blind women into shamanism. According to this legend, the practice began in an undetermined era when blind children were killed every 5 years. A local official, impressed with a blind woman's ability to describe her environment despite her lack of vision, determined that the blind must have special powers. Rather than being killed, he pressed for the blind to study necromancy.

Training

Itako were traditionally female, would start training at 11-13, at the encouragement of their parents, as a way for their daughter could contribute to the household. This was seen as an acceptable means for blind women to contribute to their local village and avoid becoming a financial burden to their families.

Training was often funded by the village, rather than the family. Training includes memorization of Shinto and Buddhist prayers and sutras. Apprenticeship typically lasts 1-4 years. During this time, the itako-in-training is essentially adopted by a practicing shaman, and performs household work for the family

In preparation of the initiation ceremony the itako must endure a 100-day fast. She is not permitted to consume grain, salt, or meat

In the last 3 weeks this is more strictly observed. The itako dresses in a white kimono similar to a burial gown. She must avoid artificial heat. This has been described as "sleeplessness, semi-starvation and intense cold."

In some cases this involved cold-water purifying baths which in its most extreme form can involve complete, sustained drenching by ice-cold water for a period of several days. These rituals are observed by the community, which prays for a fast resolution

This process usually leads to a loss of consciousness, which is described as the moment in which a spirit has taken possession of the itako's body.

In some cases, the itako must collapse while naming the spirit. In other cases, the names of various spirits are written and scattered, while the itako sweeps over them with a brush until one of them is caught, which denotes the name of the possessing spirit.

This initiation normally takes place before the first menstruation since at a later time the union with a god is believed to be more difficult

At this point, a wedding ceremony (kamizukeshiki) is performed as an initiation. The itako trainee is dressed in a red wedding dress, has the teeth colored black and partakes in the sansan-kudo ceremony ( the triple ritual sipping of sake). Red rice and fish are consumed to celebrate her marriage to the spirit.

Until quite recent times the marriage was consummated by a Shinto priest taking the place of the deity.

It is suggested that the ceremony signals the death of the itako's life as a burden and her rebirth as a contributing member of the community

After the ceremony, the Itako retires for 8 more days into the isolation of a shrine and is then ready for the practice of her profession. When someone dies in the village, she visits the family of the deceased in order to call back the soul, or people come and visit her when they want a message from the hereafter.

Tools of the Trade

Itako typically carry several artifacts:

- Gehobako: box outside of Buddhist law: Its contents are kept in strict secrecy, but it was found out that they have something to do with the personal protective spirit of the women. The contents include small figures, a representation of an embracing couple, skulls of cats, dogs and sometimes even human beings

- Blacker describes an old folk tale tying the box, and its contents, to an "inugami" ritual: a dog is buried up to its neck, and starved, while staring at food too far for it to reach. The itako place the animal's skull into a box and offer its spirit a daily offering of food. In return, the spirit enters homes of her patrons and provides detailed information about the dead.

- A black cylinder: On their backs the women carry a black lacquered tube often bamboo, containing another protective charm and their certificate of itako training. The cylinders are said to be used to trap the spirits of animals that attempt to possess a human being.

- beaded necklaces (irataka nenju), which are used in ceremonies and made up of beads and animal bones. The bones are typically jaw bones of deer or foxes, but have also included bear teeth, eagle claws, or shells

Some of the necromancers have bows instead of rosaries, whose strings sing as they pluck them. Others have two simple puppets, called O-shir asama, which they make dance

Powers and Practices

Itako are said to be able to communicate with kami and the dead. Ceremonies vary, but typically itako are called upon to communicate with kami to garner favor or advisement on harvests, or to communicate with the spirits of the dead, particularly the recently deceased.

Kuchiyose: The ritual for contacting the dead

Kuchiyose, has been named an intangible cultural heritage asset of Japan. The ritual has been documented as early as 1024 AD. The ritual is held during a funeral or anniversary of a death

During the ceremony, purifying rice and salt are scattered, and a spirit is said to enter the body of the itako. Gods are asked to compel the desired spirit to come forward. Calling the dead is usually performed in reverse hierarchy of power, beginning with kami and rising to the level of ghosts. The local kami is called forward to protect those attending the ceremony.

During the summoning of the deceased, the itako sings songs, called kudoki, said to be relayed by the contacted spirit. The spirit of the dead arrives and shares memories of its life and the afterlife, answering questions for patrons. Then, the spirits are sent away, and songs are sung about "hell, insects, and birds." A final spell is repeated three times:

"The old fox in the Shinoda woods, when he cries during the day, then he does not cry in the night"

The interaction lasts about 15 minutes

Petitioners, mostly simple fishermen or farmers, are deeply impressed by the whole scene and very often break into tears, together with the necromancer. A young woman from Morioka who has had 10 different invocations with different necromancers expressed how consoling it was. She said that even if many of their pronouncements were not relevant, still, the few true words were sufficient to console the bereaved. (only 2/10 provided something relevant )

Mizuko kuyō

Mizuko kuyō is a ceremony performed for mothers who have lost their children in childbirth or through abortions. The ritual gives the unborn or stillborn child a name, and then calls upon the protection of the spirit Jizo. The ceremony is considered by many to be a scam, preying on grieving mothers, owing to its relatively recent origins in the 1960s. Others, however, see the practice as addressing a spiritual need created by Japan's legalization of abortion in 1948

Place in Society

Despite this power, itako were still considered to occupy one of the lowest social strata within the community, especially those who relied on community support for financing their training

The term "itako" has associations with beggars, and some mediums reject the use of the term. One theory suggests the term derived from "eta no ko", or "child of the eta", referring to the Japanese burakumin social class who were once associated with death.

Visitors to the itako typically bring fruit, candy or other gifts, and offer the age, relationship, and gender of the deceased, but not the name.

History

1603 - 1868 (Edo)

During the Edo era, women were expected to contribute to family wages. However, blind women of the era had limited opportunities. This provided a career option for them

1868 - 1912 (Meiji)

1873: The government attempted to ban itako, claiming them charlatans taking advantage of good people for their money and spreading lies that their health and personal problems were caused by cats and foxes, all in an effort to encourage the use of modern medicine. There was ~200 Itako practicing at the time and law led to the arrest of mediums across Japan; by 1875, itako and their healing rituals were specifically targeted and could be arrested on sight.

Arrests were justified with charges such as spreading superstition, to obstruction of medical practices. Newspapers of the era refer to itako in negative terms often associating them with prostitution.

Professor Hori from Tokyo University draws attention to the connection between necromancers and prostitutes. Many necromancers were nomadic. Some seemed to have acted as prostitutes, indicated by the word yujo ( prostitute ) but may have been mix-ups with the term yuko-suru josei ( i.e. traveling woman). There is a similar institution of the ichiyo-tsuma (i.e. one-night wives ) It was their task to make themselves available to traveling gods (marebito) This would also explain why pleasure quarters are so often found in the neighborhood of Shinto shrines and prostitutes so fervently participate in shrine festivals.

1945

Shortly before and after the surrender of Japan in WW2 families sought out itako to communicate with the war dead, particularly those lost abroad. Some even requested live seances for soldiers overseas. Some areas stopped enforcing the laws against these women, while in others local residents would interfere in attempts to arrest them

Today

Today Itako are most commonly associated with Mt. Osore in Aomori prefecture known locally as "Mount Dread". An extinguished volcano, where no trees, plants or animals live (including birds). At the top is a small Zen temple called Entsuji, Founded in 1678 by Emperor Reigen.

The temple is open only in the summer, since it's popularly believe to be the residence of the dead, who can easily be contacted at the yearly All Souls Day (O-bon). Every year necromancers from gather between the 20th and the 25th of July to assist those who visit the temple in establishing contact with the dead.

The gathering has received televised news coverage since the 1960s

They also attend the summer festival at Kawakura Sainokawara.

Despite the disavowal of many religious organizations and temples in Japan, both events have become tourist attractions that attract crowds of hundreds. The local government includes the image of an itako in its tourist brochures, and attempted to fund a permanent itako position in the nearby temple to encourage sustained tourism throughout the year.

In contemporary Japan, itako are on the decline. In 2009, less than 20 remained, all over the age of 40. Itako are increasingly viewed with skepticism and disdain, and contemporary education standards have all but eradicated the need for specialized training for the blind.

Only four graying itako appeared at Mt. Osore's weeklong summer festival in 2009, three having died of old age in the year prior. Worse, the only practicing medium younger than retirement age 40-year-old Keiko Himukai, known among believers as the last itako stopped coming in 2009 for health reasons.

Now, there are so few itako that visitors routinely wait in line for several hours to see one. Itako charge 3,000 yen, or about $30, for each spirit called in a roughly 10-minute ceremony.

Ms. Himukai, says she enters a trance in which she feels the presence of the spirit and its mood, which she expresses in her own words. She said she decided to begin the three-year period of study to become a spiritual medium as a teenager, after an itako near her rural village cured her of an ailment that doctors could not fix.

"We can see a very ancient flame dying out before our eyes," Ms. Himukai said in a separate interview. "But traditions have to change with the times."

Shojiro Kurokawa, 82, can remember as a child in the 1930s when residents of his and other nearby villages would trek to the temple to hold weeklong festivals of all-night dancing, singing and séances. In those days, he said, there were more than 100 itako.

"This is an era when children ignore their parents and forget about the dead," said Mr. Kurokawa, who runs an inn near the temple that caters to visitors of the spiritual mediums.

Itako, though few in number, have formed an association, the itako-ko and do occasionally work with Buddhist temples, usually providing support for funerals.

Similarities

There are similarities to the female shamans, the kamisama. Both kamisama and itako believe in a marriage to a spirit, and both follow the Buddhist deity Fudo Myoo. However, kamisama are sighted, typically claiming prophetic powers in the aftermath of a traumatic disease. Unlike itako, they are associated with small Shinto shrines, which they may operate themselves. Kamisama tend to view itako with suspicion, though ethnographers have found that kamisama often associate themselves with itako and itako traditions

Pop Culture

While the actual practice of these beliefs and rituals has greatly declined with the years, glimpses of these once very important traditions can be seen in Japan's vibrant and expansive pop culture

Magical Girls

Think of all the anime with a magical girl (or group of girls) who has an animal companion, these are directly inspired by the stories of witches with their animal familiars

The magical girl is a common genre in Japanese pop culture. Usually focused on a girl or a group of girls with magic powers which typically align more with western depictions of magic. Evil witch antagonists are often inspired by the European vision are also quite popularly, but their power rarely comes from worshipping devils

Mikos, Itako and Shaman

The iconic red and white shrine garb of a miko stands out and I am sure if you have consumed any Japanese media, at one point you will have likely seen a miko. Two prevelant ones that come to mind from the animes/mangas Sailor Moon and Inuyasha

In Sailor Moon, Sailor Mars works at a Shinto shrine in her day-to-day life as a miko and uses 'spells' and rituals from her training to help banish and detect evil. As for Inuyasha, the main character Kagome's family owned a shrine where she helped out, but on her 15th birthday she was pulled inside a nearby well and transported back 500 years.

She would discover that she is a reincarnation of a feudal era miko, Kikyō. In the past she adopts the miko role and teams up with a colorful cast including: Inuyasha (half dog demon), Shippō (kitsune), Sango (a yokai hunter (demon hunter)), Kirara (a nekomato (similar to a kitsune)), Miroku (a yamabushi)

As for Itako and shaman? Well we have Shaman King

A manga and anime, where the main character Yoh is a shaman in training and is determined to become the Shaman King, so that he can make contact with the great spirit. To do so he must win a tournament which is held once every 500 years, winning the tournament will give him the title Shaman King and allow him to reshape the world however he wishes. The tournament pits shamans from all around the world against each other, each using a companion spirit to help them in battle, Yoh's companion being an ancient Samurai, Amidamaru

Yoh's grandmother was an itako who trained his friend and love interest Anna, this training giving her the power to channel spirits from anywhere. Unlike traditional Itako she is not blind

The anime was recently rebooted by Netflix!

And that's only a tiny peak into expansive pop culture of shamanism and witchcraft in Japan

Conclusion

Japan's realm of spiritual and magical lore, history and culture goes far beyond what is mentioned here. This just provides a glimpse into some of the more common practices. Many of Japan's practices have not been made available to english speaking audiences and the hundreds of small communities across the island(s) each have their own tales, beliefs and traditions that have never left their town's borders. We in the western world may never know how deep that rabbit hole goes, but from what we can see it is rich with culture and a fascinating look at a society built on strong foundations of spirituality

While active practitioners continue to dwindle, many are fighting hard to preserve, record and explore these traditions, before they disappear completely. Whether that be historians, archeologists or manga artists. It's important that these things are not forgotten, both the good and the bad, it's the only way we can advance as a society

Full Source List

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asian_witchcraft

- https://www.onmarkproductions.com/shamanism-nanzan.pdf

https://www.cavernacosmica.com/witchcraft-in-japan-the-roots-of-magical-girls/

https://hyakumonogatari.com/2013/07/02/tsukimono-the-possessing-thing/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burakumin

- https://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00385/

- https://faculty.humanities.uci.edu/sbklein/ghosts/articles/CatalpaBow-WitchAnimals.pdf

- https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/21/world/asia/21japan.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitsune

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakini

https://hyakumonogatari.com/2014/03/11/jakotsu-baba-the-old-snake-bone-woman/

https://honeysanime.com/what-are-mikos-shrine-maidens-definitionmeaning/

https://www.shikokutours.com/attractions/people-of-shikoku/En-no-Gyoja

https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/itako-the-blind-women-who-talk-to-spirits/