A Plague of Locusts

The year is 1874, you're working the fields, miles in each direction are rows of corn, wheat, barley, flax. Crops you, your family and your community depend on to survive the winters. As you pull weeds you see a large grasshopper land next to you, about 3 inches in length. As it begins to gnaw on a nearby plant, you hear a dull thrumming in the distance a sound vaguely familiar, how long has it been? 8 years?

The thrumming grows louder until it's a roar that drowns everything else out. You look across your crops and see your family members have all stopped their work as well to stare up to the sky. A shadow spills over the field and you watch as the sun is blotted out by millions of flying insects

All around you, you hear the rustling thuds as the locusts land, clinging to whatever they can find, including you. You jump into action, yelling instructions out to the others but not able to hear even your own voice over the thundering insect wings. You scramble for blankets, tarps, anything to try and save as many of the crops as you can.

Episode: File 0029: Hell: Locusts with a Chance of Meat Showers Pt. 2

Release Date: May 28th 2021

Researched and presented by Cayla

When you've done all you can, you and your family huddle in your home, listening to the insects crash against your windows, walls and doors

Days pass before the swarm moves on to the next farm, your crops are all but destroyed and your ears are ringing though the sound stopped long ago.

This is what it's like to experience a flight of locust

In 1874 North America experienced what is believed to be largest mass of living insect matter every witnessed by modern man. The storm measured 110 miles wide, a 1,800 long, stretching from the Canadian plains to the Texas border

The living, breathing tonnage of these insects in the 1874 outbreak has been compared to that of the American bison of the same era, and possibly was just as influential on the ecology of this vast region.

Over the next three decades, swarms still appeared, but in smaller and smaller amounts. Until the last known sighting of a living North American locust was in Manitoba in 1902 and there hasn't been a swarm since

What is a Locust Plague?

And the fifth angel blew his trumpet, and I saw a star fallen from heaven to earth, and he was given the key to the shaft of the bottomless pit.

He opened the shaft of the bottomless pit, and from the shaft rose smoke like the smoke of a great furnace, and the sun and the air were darkened with the smoke from the shaft.

Then from the smoke came locusts on the earth, and they were given power like the power of scorpions of the earth.

They were told not to harm the grass of the earth or any green plant or any tree, but only those people who do not have the seal of God on their foreheads.

They were allowed to torment them for five months, but not to kill them, and their torment was like the torment of a scorpion when it stings someone.

And in those days people will seek death and will not find it. They will long to die, but death will flee from them.

In appearance the locusts were like horses prepared for battle: on their heads were what looked like crowns of gold; their faces were like human faces,

their hair like women's hair, and their teeth like lions' teeth;

they had breastplates like breastplates of iron, and the noise of their wings was like the noise of many chariots with horses rushing into battle.

They have tails and stings like scorpions, and their power to hurt people for five months is in their tails.

Revelation 9:3-10

English Standard Version

After the Civil war, settlers fled to Kansas in hopes of finding a better life and taking advantage of the inexpensive land. But in the summer of 1874 those dreams would be invaded

"The insects arrived in swarms so large they blocked out the sun and sounded like a rainstorm. They ate crops out of the ground, as well as the wool from live sheep and clothing off people's backs. Paper, tree bark, and even wooden tool handles were devoured. Hoppers were reported to have been several inches deep on the ground and locomotives could not get traction because the insects made the rails too slippery." >> Kansas Historical Society June 2003

The Kansans refused to be defeated, trying anything they could to stop the swarm. Raking locusts into piles like leaves and burning them was a common method, but one that was in vain due to the sheer numbers. The locusts would stay between 2 days to a week, depending on their mood. The effect of these swarms were devastating, but not just that, the newer settlers who weren't fully established, were the worst hit. They had no stores of food, these crops were needed for them to start their lives. They needed to feed their families and livestock, they needed to be able to trade for goods and clothing to make it through the winter

It took assistance from across the country to help the Kansans that were left destitute by these swarms.

So What are They?

It was long thought that locusts were just a super mutation of a common grasshopper that occurred during the stresses of overpopulation and drought. But Jeffrey Lockwood, entomologist and grasshopper specialist of University of Wyoming, through extensive tests has posed a very strong hypothesis that that's not the case at all and that locusts are their own specific species of grasshopper

Rick Overson of Arizona State University's Global Locust Initiative explains that while there are hundreds of species of grasshoppers only a small handful of those that are considered locusts

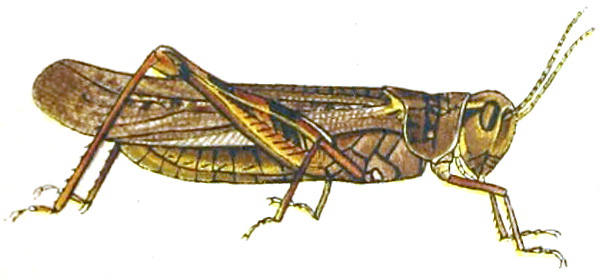

Locusts are grasshoppers that have an additional state of development. Typically locusts exist in their grasshopper phase and live like this, alone for years.

Though they have teeth, locusts don't bite humans. (Unless you, you know, jammed a finger into its mandible; it would maybe bite you then, Overson says.)

Where Did They Go?

The North American locust is very likely extinct, with no living records since 1902, making North America the only other continent aside from Antarctica that does not get even the occasional flight of locusts

The disappearance has baffled entomologists and ecologists as this extinction occurred prior to the advent of synthetic insecticides (like DDT) or even modern farming techniques

The current theory is that the species was wiped out by a series of developments that played out between 1875 and 1900 in the valleys of the upper river basins along the Northern Rockies-the natural home range of the locusts between irruptions out onto the prairies.

Here are some examples of the changes that occurred:

- loss of beavers due to the fur trade increased flooding.

- Valleys that became the homes of cattle and sheep had their native grasses replaced by alfalfa and other livestock crops.

- With the gold and silver mining boom, a fairly large number of people came to these valleys causing local agriculture expand rapidly to support the growing populations

According to this theory, the environmental disturbances in these areas caused a natural population bottleneck for the locusts. While they waited for the next drought, grasshopper eggs were trampled by livestock or flooded by spring torrents or agriculture irrigation. The isolated populations of these locust grasshoppers that were spread among these valleys couldn't hold out against these factors

It took a while before we noticed that the locusts were gone, as usually they only swarm about once every decade and with WWI and the great depression, to say scientists were distracted was an understatement.

So is this insect truly gone forever? Daniel Otte, a well respected authority in the field argues no. He believes that locust still exists, just lying dormant, hidden in remote valleys waiting for the perfect conditions to re-emerge as the agriculture terror it was meant to be

Otte is a senior curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences at Drexel University in Philadelphia and is well known for his studies on grasshoppers and crickets as well as on the origin of insect species. According to his website he has discovered and named roughly 1,600 species and is the author of a 2-volume atlas, North American Grasshoppers published by Harvard.

This begs the question, as posed by Lockwood, if there does happen to still be some remnant populations waiting to be found, would they be protected by the Endangered Species Act? Generally insect pest species are not viewed as eligible protection but it's an interesting idea to entertain.

If the species were to make a comeback it could be devastating. Lockwood compares the locusts to the smallpox virus. How its kept in small samples in specific labs, that if any locusts were found there would be plenty of scientists that would argue to acquire live samples to observe and study in a controlled and sealed environment. Release back into the wild just wouldn't be acceptable.

But there are those among entomologists who think that when (not if) the locusts return it will not be small and quiet. Locusts have survived ice ages and dinosaurs. And in other parts of the world they're still thriving despite powerful pesticides and genetically manipulated crops. To them, it's just a ticking time bomb until the right conditions are met to make a grand return

The Rest of the World

Then the Lord said to Moses, "Stretch out your hand over the land of Egypt for the locusts, so that they may come upon the land of Egypt and eat every plant in the land, all that the hail has left."

So Moses stretched out his staff over the land of Egypt, and the Lord brought an east wind upon the land all that day and all that night. When it was morning, the east wind had brought the locusts.

The locusts came up over all the land of Egypt and settled on the whole country of Egypt, such a dense swarm of locusts as had never been before, nor ever will be again.

They covered the face of the whole land, so that the land was darkened, and they ate all the plants in the land and all the fruit of the trees that the hail had left. Not a green thing remained, neither tree nor plant of the field, through all the land of Egypt.

Exodus 10:1-19

English Standard Version

2020 was a rough

year, with the outbreak of Covid and the hits just kept coming from every

direction. But did you know it also brought locust plagues with it?

Titanic swarms of desert locusts resembling storm clouds descended on the Horn of Africa. They're roving through croplands and flattening farms in a devastating salvo experts are calling an unprecedented threat to food security.

In an NPR article from June 2020, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organizations warned that if the locusts keep up with projections at the time, they could threaten the livelihoods of 10% of the world's population

Many of the areas hit haven't had a major infestation in decades

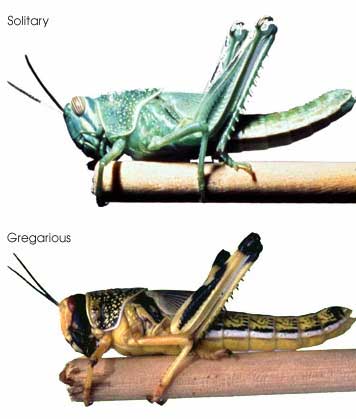

So what causes the desert locust to endure this transformation into devouring hordes, when the vast majority of grasshopper species are solitary creatures?

That might have something to do with the dry environments these species call home. Desert locusts only lay eggs in moist soil, to keep them from drying out. When heavy rains come in to saturate the desert, locusts-ever the opportunists-breed like mad and fill the soil with their eggs, perhaps 1,000 per square meter of soil. When those eggs hatch, they'll have plenty of vegetation to eat, until things dry up once again.

As soon as things start getting crowded, desert locusts become gregarious and migrate away in search of more food.

"If they were to stay locally, one potential is that there are too many of them and they would run out of food," says Cease. "And so they migrate to find better resources."

By doing so in swarms, the locusts find safety in numbers-any individual is less likely to get eaten. But for farmers in surrounding countries, the locusts' newfound mobility can spell ruin.

Overson explains that when the conditions are just right, usually when there's a lot of rainfall or moisture. They increase in numbers and sensing each other

"Their brain changes, their coloration changes, their body size changes," Overson says. "Instead of repelling one another, they become attracted to one another - and if those conditions persist in the environment, they start to march together in coordinated formations across the landscape, which is what we're seeing in eastern Africa."

To adapt to this new social life, the locusts' bodies transform, inside and out. They change color from a drab tan to a striking yellow and black, perhaps a signal to their predators that they're toxic. Indeed, while solitarious locusts avoid eating toxic plants, the gregarious locusts are actually attracted to the odor of hyoscyamine, a toxic alkaloid found in local plants. Sure, by eating those plants and assuming their toxicity and changing color to yellow and black, the insects make themselves more conspicuous, but that isn't such a big deal when there's millions of them barreling across a landscape-no one's trying to hide.

The ability to change dramatically like this in response to environmental conditions is called phenotypic plasticity. Many species, such as some types of coral, exhibit it. Though scientists can't be certain why locusts developed the trait over time, many believe it's because they typically live in temperamental and harsh environments.

"Locusts tend to live in areas where resources that they need are very unpredictable," Overson explains. The Horn of Africa, for instance, is known for being arid, going for years without heavy rain until slammed suddenly by powerful downfalls. "The strongest hypothesis is that these crazy, unpredictable dynamics select evolutionarily for this ability to go through these dramatic changes, to respond when you can capitalize on a rare opportunity and also have capacity to migrate."

When locusts swarm like this, they ravage agriculture, devouring practically anything in sight.

Swarms are most intense in East African countries, including Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia, but data from the FAO's Desert Locust Watch documents steadily worsening infestations across Southwest Asia and the Middle East. Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Uganda and Iran are among those afflicted.

"In Kenya, it's the worst outbreak they've had to face in the last 70 years," says Keith Cressman, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization's senior locust forecasting officer. "In India or Pakistan, it's probably the worst they've had to face in the last quarter of a century."

Egyptian farmers are burning tires to dissuade locusts blown in from the Sudan. Israel is similarly affected. The cradle of agriculture and civilization along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers is still occasionally visited by locust swarms.

The swarms are gargantuan masses of tens of billions of flying bugs. They range anywhere from a square third of a mile to 100 square miles or more, with 40 million to 80 million locusts packed in half a square mile. They bulldoze pasturelands in dark clouds the size of football fields and small cities. In northern Kenya, Cressman says, one swarm was reported to be 25 miles long by 37 miles wide - it would blanket the city of Paris 24 times over.

Experts say the upsurge is likely to be tied to extreme weather events: According to Cressman, powerful cyclones in 2018 dumped water in Oman, Yemen and the Horn of Africa. The wet conditions have persisted, creating ideal bug breeding conditions

Locusts are migratory, transboundary pests. They ride the winds, crisscrossing swaths of land until they find something they want to munch on. They especially love cereal grain crops, planted extensively across Africa.

"They are powerful, long-distance flyers, so they can easily go a hundred plus kilometers in a 24-hour period," Overson notes. "They can easily move across countries in a matter of days, which is one of the other major challenges in coordinated efforts that are required between nations and institutions to manage them."

In 1988 swarms from North Africa cross the Atlantic Ocean made it to the Caribbean and South America. Even today, they routinely traverse the Red Sea - a distance of 186 miles.

Locusts are ravenous eaters. An adult desert locust that weighs about 2 grams (a fraction of an ounce) can consume roughly its own weight daily. And they're not picky at all. According to the FAO, a swarm of just 1 square kilometer - again, about a third of a square mile - can consume as much food as would be eaten by 35,000 people (or six elephants) in a single day.

"When they do descend, they can have almost total devastation," Overson says. "They can cause 50 to 80% of crops to be destroyed, depending on the time [of year]."

The last big outbreak went from 2003-2005 resulting in $2.5 billion in damages. Not only did this impact the economy, but children who grew up during the period were much less likely to go to school, and girls were disproportionately affected.

To make matters worse, the countries that are slammed with these infestations are countries that are already struggling from recessions, natural disasters, internal conflict and now covid.

"We're talking about a corner of Africa that's really, really vulnerable," Cressman says. "They've had successive years of drought, and then this year, they've had heavy rains and floods. So even without the locusts, they're already in a precarious situation."

"The locusts are in your field for a morning, and by midday, there's hardly anything left in your field," he says. "It's just eaten."

The biggest challenge for individual nations is lack of cash. Due to inconsistencies and ebb and flow of swarms, you never know when a swarm is going to hit. Prior to this Kenya hadn't seen a swarm in 70 years. It makes it hard to motivate long-term proactive solutions when there's so many other urgent challenges

"It's hard to maintain funding and political will and knowledge and capacity building when you have these unpredictable boom and bust cycles that could play out over years or decades," he says. "The drama and spectacle of the outbreak right now is important to cover, but the more nuanced narrative involves the slow, ratchet method of building infrastructure: If you wait until it's reactive and forget about it until it happens again, we're going to be in this situation forever."

The most effective way we have to fight these outbreaks currently is mass aerial sprays of pesticides. But this solution is heavy with adverse effects to the environment and the humans that live near these areas

But there is new technology that is being developed that show promise, including biopesticides:

There are 4 classes of biopesticides:

- Microbial pesticides which consist of bacteria, fungi or viruses

- Bio-derived chemicals: there are four that are in commercial use: pyrethrum, rotenone, neem oil and various essential oils

- Plant Incorporated Protectants (PIPs) uses genetic material from other species and incorporated into the target crops that need protection. This is very controversial, especially in european countries

- RNAi pesticides: either applied topically or absorbed by the crop

Many plants have their own defenses against different pests, by examining other plants and the chemical compound that help them naturally deter pests, we can use this to develop more natural solutions

A new biocontrol method, though, is showing promise. The killer fungus Metarhizium acridum, which only torments locusts and grasshoppers, could more selectively target the menace.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization is partnering with NOAA to adapt an application they use for tracking plumes from volcanoes and forest fires to help them better predict where locusts will strike next

Knowing wind patterns can help U.N. authorities pre-position material and personnel in an effort to prevent croplands from being destroyed.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization's Locust Watch website, the swarms are currently moving through Kenya and Somalia and headed for Ethiopia, with additional swarms in Jordan, Syria and Iraq moving down towards Yemen and east to Pakistan

What's the Good News?

It's a menace that may only grow stronger, because locusts will likely be winners on a warming planet. They need a lot of vegetation to fuel their swarms, and that requires rain. The highly active cyclone seasons the past few years may be a sign of things to come. Warmer seas spawn more cyclones, and more cyclones-especially sequential ones that give locusts wet soils to breed in as they march across the landscape-could mean more locusts.

On the climatic flip side, locusts are highly adapted to a life of heat and drought: The Global Locust Initiative's experiments have shown that Australian plague locusts can survive up to a month without water. So while other species struggle to adapt to a rapidly-warming planet, the locusts will have an advantage both in their heat-tolerant physiology, and potentially from a decrease in competition from less fortunate insects.

"If climate change does accelerate aridification and temperature-as it's predicted to do in many areas-it would be very easy to imagine that some locust species could expand their range," says Overson, of the Global Locust Initiative. "For the desert locust, this would increase the already daunting geographic area that needs to be monitored."

Thanks to the donations received so far the UN Food and Agriculture

Organization has been able to develop several high tech tools for tracking,

monitoring and predicting the movement of these locusts

Previously all data collection was received from individuals on the ground,

which was frequently vague and in 25% of the cases, incorrect and unusable

Satellites may be the biggest game changer in the fight against Desert Locusts. Since rainfall is a critical component for locust breeding, FAO is using two satellites to identify rainfall and vegetation that might be attract locusts for breeding.

"It sounds like science fiction doesn't it?" says Cressman.

A third satellite which Cressman dubs the 'Holy Grail of Desert Locust monitoring' goes a step further and can detect soil moisture beneath the earth's surface, conditions which would allow the female locust to lay her eggs.

"It is not just about the moisture on the surface of the soil but also down about 15 centimetres, the depth to which females can lay their eggs," he says.

FAO is working with NASA, the European Space Agency and the European Commission's Joint Research Centre to refine the satellite technology.

Back on the ground, this satellite data is transmitted in real time across cell phones, tablets and other devices so countries can mobilize their control teams and take immediate action to tackle the locust swarms.

With these

operations, the scale of the Desert Locust invasion has vastly diminished in

Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia. In East Africa locust control operations have

prevented the loss of 4 million tonnes of cereal and 800 million litres of milk

production, while protecting the food security of 36.6 million people and

avoiding USD 1.56 billion in cereal and milk losses.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic and the arrival of the locusts, Kenyan pilot Chris Stewart used to ferry celebrities, royalty and other people to luxury hotels in exclusive conservation areas. Now he hunts locusts.

"It's easy to confuse smoke or dust clouds with a swarm, and if the insects are resting in trees they look like acacia flowers," he says.

Yussuf Kurtuma, Christine Kebaba - both employees of tech company 51 Degrees, which helps track the locusts - and Casper Sitemba are looking at a data-filled screen. In the operations room information from Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya is compiled and analyzed.

"We gather together all the information people in the villages give us," says Kurtuma. "The elders and the trackers employed by various different companies collect it. We compile all of this information in one platform and then we share it with all of the people working on the ground to stop the desert locusts."

"While the situation has improved, with few swarms remaining in Kenya and less numerous and smaller swarms in Ethiopia and Somalia, we are still not yet at the end of the upsurge," says Cyril Ferrand, FAO's Resilience Team Leader for Eastern Africa.

"We are now in the middle of the rainy season and although rainfall has been below average, conditions are becoming more favourable for Desert Locusts to breed. It is paramount to maintain a high level of surveillance."

The threat has also diminished in Yemen, but small swarms have recently appeared in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

FAO has won many battles against Desert Locusts, but this war is not over yet.

As a bonus! Canada donated $2 million on May 11th

2024 UPDATE

New studies may have found a way to use existing meteorological technology as an early warning system for locust swarms, and by early we're talking maybe 5-7 hours notice, but that's more than we have ever had so that's a win

Sources

https://www.reddit.com/r/askscience/comments/2qc3v3/why_dont_we_have_plagues_of_locusts_anymore_the

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelation+9%3A3-10&version=ESV

https://www.wired.com/story/the-terrifying-science-behind-the-locust-plagues-of-africa/

https://english.elpais.com/usa/2021-04-17/how-kenya-is-controlling-locust-plagues.html